This is the third part of a series covering unit economics and its importance when evaluating business health:

- Should You Acquire that Company? It Depends on the Unit Economics

- Applying Unit Economics to Cafe Acquisition

- Productizing Unit Economics

In the last blog post, we started to put unit economics into action by:

- Listing the drivers of revenue and cost, at the unit level

- Writing the governing equations of profitability

- Setting the revenue and cost equations equal to one another to reveal break-even conditions

This post will pick up where the last one left off, going from equations to an interactive . This example tool demonstrates the power of unit economics in due diligence. Teams in private equity, mergers and acquisitions, venture capital, and corporate strategy can leverage tools like the one presented here when assessing whether to acquire a company.

While some might look to Excel, I have found that unit economics comes to life when I have productized it into a fully-fledged decision-tool. Such a tool interactively updates scenario visualizations by varying input conditions. This means that multiple team members across the organization can easily assess unit economics and objectively evaluate the business model of the target company.

Without further ado, let’s proceed with step 4 of unit economics analysis: Productizing profitability scenario analysis into a decision-tool.

A Motivational Example: Streaming Music

Suppose you are contemplating acquiring a streaming music company. You might be a record label, a private equity firm, or a venture capital fund. Before spending millions or even billions of dollars on the acquisition, the operational due diligence process should answer the following questions:

- Does the business model make any economic sense?

- Would interventions by the acquiring company result in a profitable business model for the target company?

The previous two blog posts describe unit economics analysis as a powerful and reliable way to answer these questions.

Before diving into the analysis, it is worth noting that there are two primary business models in the streaming music industry:

- Ad-Supported: Users can stream music for free, but they must listen to ads in between songs.

- Subscription: Users pay a monthly subscription fee, but have no ads interrupting their music listening experience.

Note that each of these verticals has its own unit economics.

Crash Course in Streaming Music

Let’s get going with a quick crash course and glossary of terms in streaming music:

- CPM: Cost per thousand impressions to the advertiser, paid to the streaming company. This is how advertising deals are guaranteed in the industry. This is a cost to the advertiser, and a revenue for the streaming service.

- Ad Load per Hour, in “30s:” The number of 30 second advertising spots per hour of content.

- Cost per Play: The royalty fee paid to the artist by the streaming company for each time a song is played by one user.

- Average Song Length: The average duration of one piece of audio content when played once by one user.

- Subscription Revenue per User: The monthly fee paid to the streaming company from each user.

In the interest of brevity, only the ad-supported business is discussed in this blog post. But the tool covers both the ad-supported and subscription businesses.

Unit Economics for the Ad-Supported Tier

For purposes of unit economics in the streaming ad business, let’s represent 1 unit = 1 hour of streaming. In other words, one user playing music for 1 hour.

The drivers of profitability on the ad-supported side are as follows:

Revenue:

- Cost per Thousand Impressions (remember, this is a cost for the advertiser, but a revenue for the streaming service)

- Ad-Load per Hour

Cost:

- Cost per Play

- Average song length

When applying unit economics, these levers become user input controls in the tool. A user will be able to toggle between different values of each factor. For example, compare scenarios with four (4) ad spots per hour vs. six (6).

The levers of the tool are shown below:

Let’s explore when the advertising business breaks even.

Break-Even Conditions

On the ad side, revenue = cost when the CPM the streamer is paid by advertisers (revenue) equals the royalty fees paid out to artists (cost). Applying revenue and cost equations scaled to 1 hour of streaming, we can determine the set of break-even conditions.

Before using the decision-tool to reveal our break-even conditions, let’s start with some intuition:

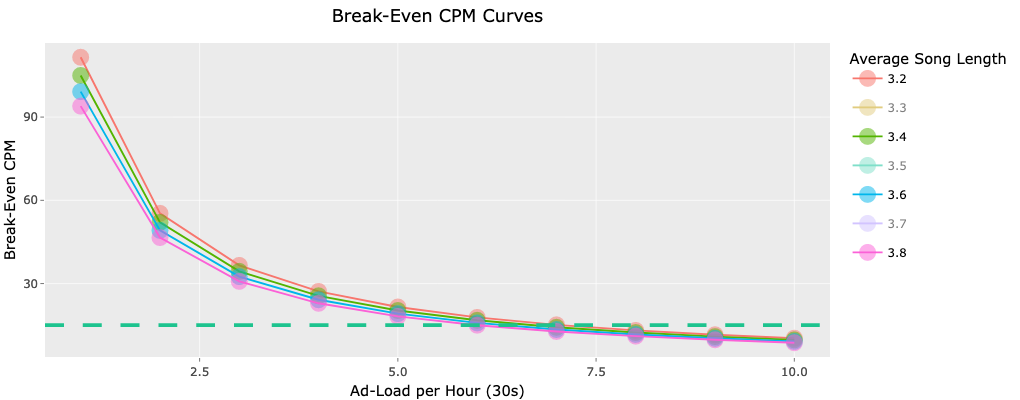

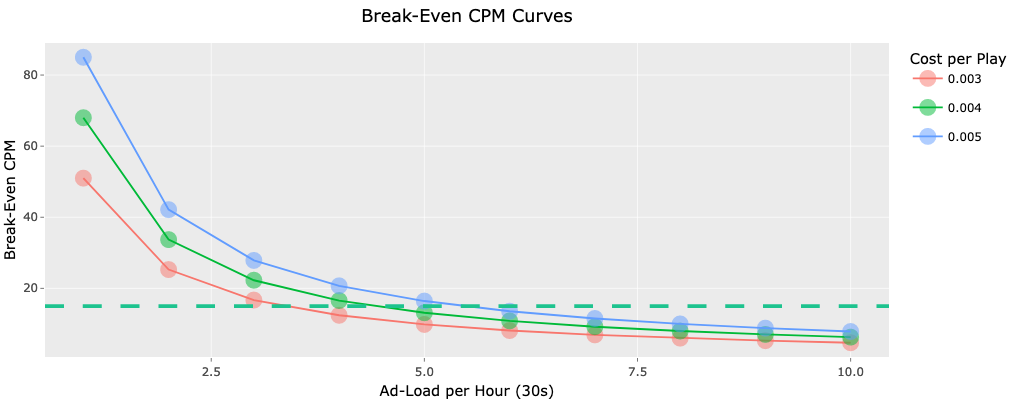

- More ads per hour → Lower break-even CPM: More ads per hour means more revenue payments, so a lower revenue rate (CPM) is required.

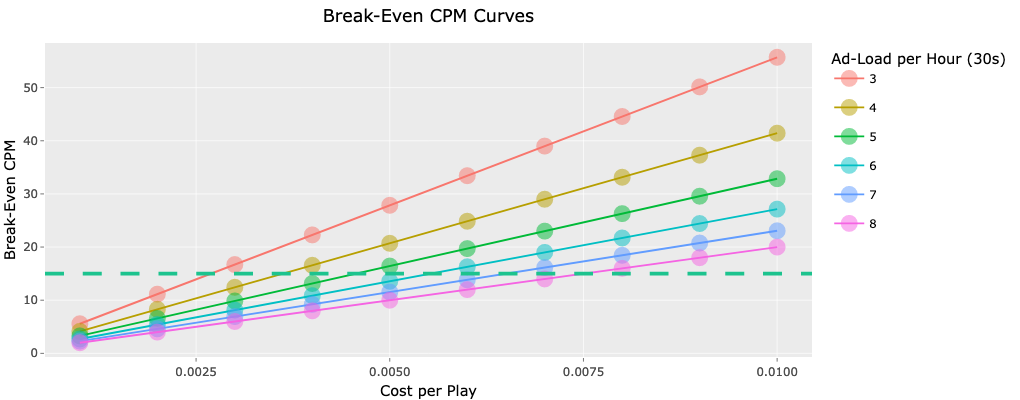

- Higher Cost per Play → Higher break-even CPM: Higher costs mean that higher revenue rates (CPM) are required to keep up.

- Higher Average Song Length → Lower break-even CPM: Longer songs mean fewer songs played per hour. Fewer plays means fewer royalty payments. Consequently, a lower CPM is required.

Break-even scenarios are most insightful in the context of realistic expectations of business conditions. In streaming music, the acquiring company can compare an expected revenue figure (CPM: rate per thousand impressions) to break-even scenarios. This empowers the deal team to determine whether a particular scenario is realistic or not. For example, if the team believes a $10 CPM is reasonable, but the scenarios under consideration require a $30 CPM, then these scenarios are not realistic. We will explore these comparisons in the tool using a dotted line across the break-even scenario curves.

willAs we explore concrete break-even conditions you might notice that there are not two (2), but four (4) drivers of unit profitability. Therefore, our equation involves four variables and our break-even profitability function has three independent variables and one dependent variable:

- Dependent Variable: CPM

- Independent Variables: Ad-Load per Hour, Cost per Play, and Average Song Length

- Function: Break-Even CPM = CPM(Ad-Load, Cost per Play, Average Song Length)

With four variables, the chart of the profitability function is a four-dimensional surface. Therefore, visualization is non-trivial, and a typical static 2-D plot won’t cut it. The decision-tool addresses this by showcasing each constituent 2-D cross section of the 4-D surface. Specifically, we can look at each of the three independent variables on the x-axis and break-even CPM on the y-axis. Additionally, we can plot “parallel” curves using another independent variable.

Each point in these visualizations is a scenario, detailing the values for all factors that result in break-even profit (E.g., 4 ads per hour, 3.5 minute songs, etc.). For example, we can chart ad-load against CPM, plotting curves by average song length. The higher the ad-load the lower the CPM, which agrees with the intuition described above. The cost per play is held constant, but the user can modify it to update the chart.

Alternatively, we could plot our curves by cost per play:

It’s worth noting that all cross-sections of the profitability function do not look the same. Here is the cross-section if we plot cost-per-play on the x-axis:

It was easy to export these visualizations using the tool. The team could discuss an exact set of break-even conditions and profitability curves. Additionally, a team-member could plot various scenarios and bring them to a board meeting for discussion.

Feel free to try out the tool here. It’s free to sign up, which will also sign you up to the Optimal Decision Dynamics mailing list.

Going From Scenario Analysis to Business Strategy

This tool is powerful not only because of the profitability conditions it can illustrate, but also by the actionable questions it can generate. Equipped with our scenario analysis tool, we can ask the following questions of our streaming services company:

- How many ads per hour of music will consumers accept?

- What is the distribution of cost per play across all artists, and how do we expect it to change over time?

- What proportion of impressions’ CPM is above, or close to, a break-even point?

- If the current CPM distribution is unprofitable, is a profitable shift expected or plausible?

At this point in the assessment process, use data and models to determine the company’s current situation - and whether a profitable scenario is reasonable to expect. Approaches like this empower deal teams to ask specific questions of the operation, and build acquisition and operating strategies around them.